No Sign of Change in Burma: Interview with Ben Rogers

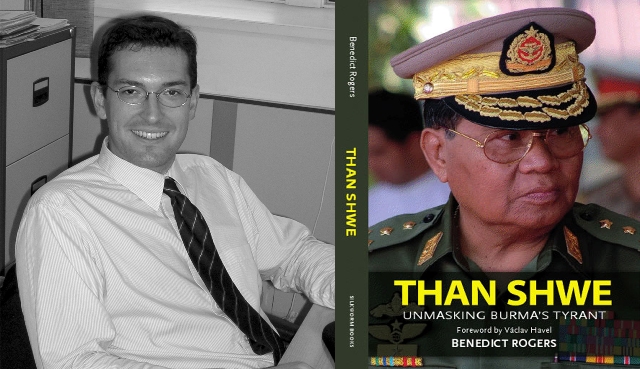

19 April 2011 [CG Note: Benedict Rogers, East Asia team leader for Christian Solidarity Worldwide (CSW), was late last month deported from Burma during his last visit to the military-ruled country.

He has travelled extensively on human rights fact-finding missions to Burma on the Thai-China-India-Burma borders as well as inside.

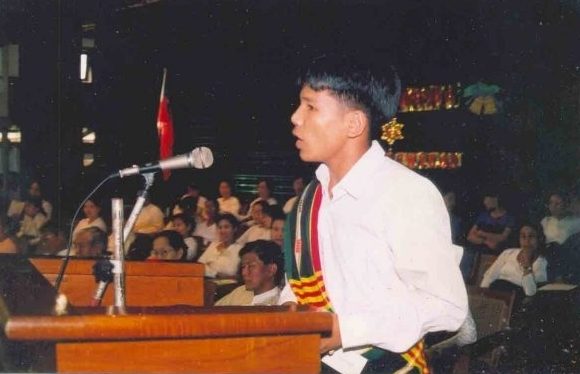

In this interview with Van Biak Thang of Chinland Guardian, a British Christian human rights advocate and author of Than Shwe’s biography talks about his recent experience, views on the situation of Burma during his trips into the country and to borders, and more …

Benedict Rogers is also the author of ‘A Land Without Evil: Stopping the Genocide of Burma’s Karen People’ and of a report ‘Carrying the Cross: The military regime’s campaign of restriction, discrimination and persecution against Christians in Burma’.]

Chinland Guardian: What did your recent deportation from Burma tell you?

Ben Rogers: It told me that nothing has changed in Burma. If the situation was changing, even slowly, then deporting a foreigner who has committed no crime, who has entered the country on a valid visa, and who had simply written a book, is no sign of change. The MI [Military Intelligence] actually said to me that there was “no change, no change” – so we have their word for it!

Chinland Guardian: So, your book ‘Than Shwe: Unmasking Burma’s Tyrant’ has been well-received by the regime?

Ben Rogers: It seems not. It was surprising that they had given me a visa, and I think someone in the system made a mistake. When I asked the MI officer whether he thought my deportation was justified, he said: “I have not read your book, so I cannot comment. I am only following my orders”. But then he asked me if I had a copy of my book with me, which was very funny. I told him I did not, but if he gave me his address I would gladly send him one. He didn’t respond.

Chinland Guardian: You mentioned that a group of ‘non-uniformed’ men met you at the hotel you were staying in Rangoon. Do you think they are people from the new government or the old one?

Ben Rogers: The system and the people are the same. There is no ‘old’ government and ‘new’ government, in reality. There are some new institutions, a few changes of personnel at the top levels, a rotation of positions, but underneath the system is the same.

Chinland Guardian: You have made several trips to Burma, both inside and borders. Share with us the different pictures that you have experienced between the two.

Ben Rogers: I have travelled many times to the different borders – the Thai-Burmese border, the India-Burma border and the China-Burma border, and once to the Bangladesh-Burma border – as well as several times inside the country. Clearly, the biggest difference is that the oppression inside Burma is more subtle. In the ethnic areas and on the borders, you hear and even see evidence of the regime’s brutality – I have met many women who have been gang-raped by soldiers of the Burma army, people used for forced labour, refugees and internally displaced people who have been forced to flee their villages. I have visited villages that have been burned down, and met former child soldiers. I’ve met people who have lost limbs from stepping on landmines, sometimes after being forced to work as human minesweepers. I’ve also met former political prisoners.

Inside the cities in Burma, the oppression is still severe, and economic deprivation is dire, but the suffering is less visible and less physical. Also people are more frightened to talk than they are on the borders, although some people do talk.

People in the cities are less aware about what is happening in the ethnic areas – they don’t necessarily know the extent of the suffering.

I have deliberately travelled to all the borders and inside the country, because I think it’s really important to see Burma and the issues as a whole. There is too much division and polarization. Too many people, sometimes through no fault of their own, are too narrow in their perspectives. Rangoon-based people are Rangoon-centric, border-based people are focused, understandably, on the border, but we need people who see and understand both, and have a complete picture of the regime’s oppression of its people. For Burmese and ethnic people, their lack of understanding of each other is primarily due to lack of information and communication, and that’s something perhaps outsiders can help with. But for foreigners – diplomats, NGO workers and others – they have less excuse. There needs to be more effort by Rangoon-based foreigners to understand the ethnic issues and the border situations, and – where possible – foreigners working on the borders would do well to travel to Rangoon from time to time as well.