The plight of the Chin people: Struggling with 2Cs

(Photo: IDPs taking shelter in a jungle near the Indian-Myanmar border in Thantlang Township)

By Sui Meng Par

10 July 2021

In the morning of 1st February 2021, the majority of Myanmar nationals apparently woke up not knowing what had exactly happened. For some people, the fact of the military staging a coup was left unknown till noon, with the sudden loss of mobile phone services although the internet communication remained normal in Myanmar.

A 40 year-old who had bitter experience from the previous military rule said on condition of anonymity:

“I learnt the news about Myanmar’s military coup from my friend at around 9am in the morning on 1 February 2021. Hearing the word “military coup”, I felt my thoughts immediately went back to the olden days and could visualize the agonies all over again in the country’s long miserable history. My feelings were mixed up with frustration and sorrow. I felt that our future(s) became once again blurred.”

In Chin State on 7th February 2021, news of the military coup was taken over by that of anti-coup peaceful public marches in Hakha, Chin State’ capital. Another 6 townships at once joined the movements the next day. Peaceful protests met with brutal crackdowns and arrests by the junta’s forces. In the first incidents, as reported by Chin Human Rights Organization (CHRO), the riot police arrested three persons including CEO of the Hakha Times, a local news agency, in Hakha on 27th February, and used teargas and smoke bombs to disperse peaceful protestors in Falam on 28th February. By then, throughout the country, many people were shot dead and many more arrested for expressing their opinions on the streets. As of 9th July 2021, at least 899 lost their lives and 5,141 people were currently under detention, according to Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma).

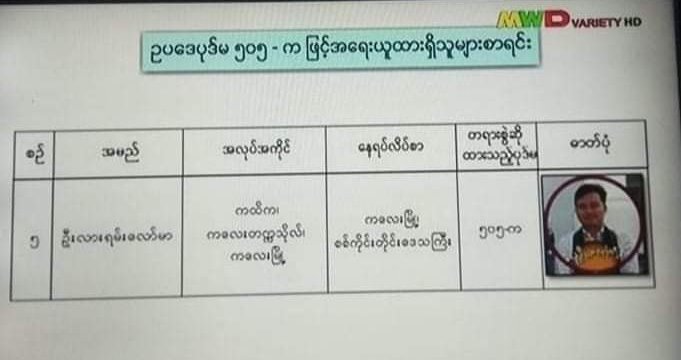

Many fled the country for security reasons – including government employees who had joined the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). Arrest warrants were issued for some of them, dubbed CMDers. They were forced to flee to neighboring countries such as Thailand and India as the illegitimate rulers, self-appointed members of the State Administration Council (SAC), started issuing warrants for mass arrests. At the same time, the military still conducted arbitrary arrests without any warrants. Armed soldiers and police with the help of military informants raided private houses day and night, made arrests and pressed charges against them with Section 505(A) of the Penal Code, which could lead to an imprisonment of up to 3 years.

Some were arrested or hunted for after being accused of financially assisting CDMers while others for being directly involved in disrupting what they [junta] called “the stability of the nation”. According to CHRO,at least 163 Chin civilians still remain in police and military custody even after the recent amnesty granted on 30th June 2021.

Following the coup, Myanmar has seen an increasing number of displacement in the country. In India alone, thousands have taken refuge, especially in the border State of Mizoram. In recent reports according to the Mizoram government, more than 15,000 people from Chin State including members of the Myanmar parliament, have reached India, with the majority staying in Aizawl, Lunglei, Siaha, Champhai, Lawngtlai Districts of Mizoram State.

However, India is not a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol, and does not have any domestic laws of its own to protect refugees. The Indian government’s unwelcoming policy towards the inflow of refugees and its subsequent deployment of Assam Rifles along the Indo-Myanmar border (border guarding force) has left refugees without much choice but to sneak into the country through dense forests and steep mountain slopes on foot across Tiau River. To the contrary, the Mizoram State government, despite its limited power from the Central government and its current struggle in the fight against COVID-19 pandemic, indicated that it should not ignore the catastrophe in its backyard while providing humanitarian aid for refugees.

There has been a concerted effort made by non-governmental organizations in Mizoram including the Young Mizo Association (YMA), Mizo Student’s Association and Young Mizo Association, CDM supporting groups and Chin diasporas abroad in reaching out to refugees. In addition, makeshift camps are being built near Farkawn and Vaphai villages, Champhai District, to shelter refugees from Chin State, Myanmar. As the monsoon reason has started, the situation has become more difficult for refugees facing challenges in food supply and basic amenities. Recently, Reuters reported that “as many as 1,621 people from Myanmar have taken shelter in a community housing complex in Aizawl”. Myanmar refugees living in the capital of Mizoram State, however, encounter different problems including language barriers, financial issues and transportation that requires legal documents.

Many refugees seeking shelter in Aizawl City are government employees (CDMers) who had left behind their primary source of income. Of all the CDMers, only a few could rely on remittances from relatives living abroad. However, this would not be a long-term solution. Other CDMers mostly depend on the humanitarian assistance given to them by CDM supporting groups in Aizawl to meet the needs for survival. A monthly assistance of Rs. 2,000 (approximately 40,000 MMK) remains inadequate for many families. To the worse, the initial hope of finding employment for surviving, for instance in manual works, becomes unrealistic because of strict COVID-19 constraints in the host country.

Despite the linguistic similitude between Mizo and Chin languages and the ethnic ties shared by the two tribes, language barriers remain a big issue for some refugees settling in a new place. This has actually put many refugees in difficulty, especially when getting access to basic services, particularly related to health issues. They have to wait for long hours until interpreters are available to accompany them to clinics or hospitals. In fact, this raises a big concern in emergency cases.

With the prolonged period of total lockdown in Mizoram State, many people get stuck in small spaces, hardly having any chances to access basic necessities, let alone renting a place to move houses. A lot of people feel helpless with COVID-19 policy affecting travels within Mizoram State.

A wife of a refugee police force (CDMer) interviewed said:

“We shared a room with 7 other families, totaling 28 in a not-quite-large room. Families who have relatives abroad are somehow financially stable more than us. For me, I didn’t even have money to buy snacks for my 2-year-old boy. We came here believing we would earn some money doing some manual labors, but nothing worked as planned. Now that we couldn’t go back home, I think there’s nothing but to hope for COVID-19 lockdown to be over soon.”

Moreover, the second wave of COVID-19 in India can wreak havoc on lives of refugees who have already been struggling since their exodus. According to Zonet Zawlbuk on 7th July 2021, COVID-19 caused 98 deaths with a large number of new positive cases reported on a daily basis, bringing more of unprecedented crisis on the lives of refugees. At least 3 refugees from Chin State seeking shelter in Mizoram succumbed to COVID-19. Though Indian citizens started to receive Covishield vaccination, yet a charge of Rs.780 per dose at private hospitals in Mizoram remained significantly difficult for the majority of the Myanmar refugees, coupled with language and transportation barriers.

Surging COVID-19 Cases

Chin State saw an increasing number of COVID-19 fatalities and positive cases in June 2021. Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as the global pandemic in March 2020, Myanmar saw 3,419 deaths, according to the Irrawaddy on 5th July 2021.

Cikha, an Indian-Myanmar border town in the northwest of Chin State, reported a growing coronavirus outbreak in mid-May where Reuters reported “health workers fear the illness could be the highly infectious B.1.617.2 strain – though they lack the means to test for it”. Hence, it was highly suspected that this delta variant has spread from India to Myanmar, as the B.1.617.2 coronavirus variant was first discovered in India. As neighboring areas of India, Kalay, Sagaing Region and Chin State emerge as COVID-19 hot spots. The Khonumthung news reported over 20 deaths in Kalay of Sagaing Region in a single day on 9th July 2021. COVID-19 death toll in Chin State reached 65, with 1,968 positive cases as of 9th July 2021, according to CHRO.

As the Coup and COVID-19 are significantly escalating, tackling the consequences of the two Cs for the Chin people inside and outside of Myanmar remains a painful struggle. Inside the country, the junta government’ administrative mechanism fails to function effectively until today, especially in health services. The deteriorated Myanmar’s health system, since coup, have put lives under double threats and the condition of livelihoods would be worsening due to the impacts of the coup and COVID-19. On the other hand, refugees in India would continue to face difficulties as manual labors are unavailable under COVID preventive measures, alongside different barriers they have already encountered. Hence, it is highly likely that both many IDPs inside the country as well as refugees in the neighboring country will face livelihood woes.#

Sui Meng Par is a Master’s degree holder of Chiang Mai University. She is an independent researcher and currently works as an editor at The Chinland Post.