Changing the Status Quo in Burma

13 April 2011: With the formal dissolution of the State Peace and Development Council on 30th March, the Burmese junta has now ‘handed over’ the executive, legislative and judicial powers to the new government. A 69-member cabinet, headed by the president and two vice-presidents, was subsequently sworn in at the Union Parliament. This new ruling body came out of a fundamentally flawed and widely discredited electoral process, whose primary purpose was to ensure dominant positions for key junta figures in the new governing structure.

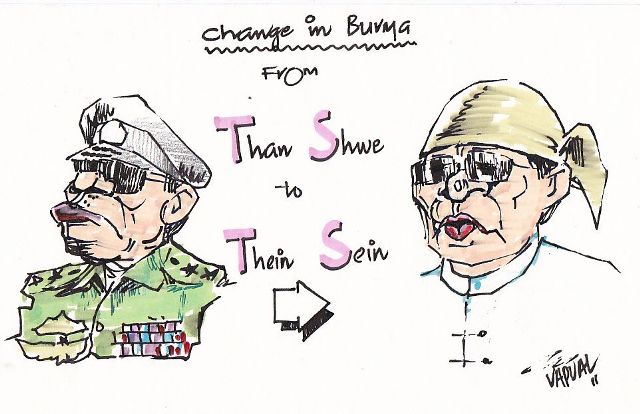

Despite the purported change, most of the same faces in the previous regime are still effectively at the helm of the new government – validating concerns expressed by the international community that Burma’s political transition would only be a change in name, rather than any substantive move towards civilian democracy.

Nowhere is this more evident than the former junta supremo Senior General Than Shwe’s current position in the new power structure. As head of the new ‘Supreme Council’ – the secret power house behind the new regime – the 78-year-old dictator will now wield power from behind the scenes. With Than Shwe at the helm, the ‘Supreme Council” is composed of top junta officials; Vice Snr-Gen Maung Aye, ex-Gen Shwe Mann (Lower House speaker), ex-Gen Thein Sein (Current President), ex-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo (Current Vice-President), ex Lt-Gen Tin Aye (Current Union Election Commission Chairman) and Min Aung Hlaing. While not directly involved in the day-to-day government administration, according to reports the Supreme Council will have enormous clout over the new regime.

An ostensible adaptation from the North Korean model, the new power arrangement will now make Than Shwe the de facto head of state of the Republic of the Union of Burma, like the North Korean dictator Kim Jong Il, who exercises exclusive power despite not being the formal head of state. As President of Burma, Thein Sein will be the de jure head of state, although with a nominally symbolic role in terms of exercising real control over the government and the country. Nonetheless, Than Shwe may have set up the new system to allow himself a plodding exit from the political scene.

But Burma’s problems are complex, and they involve many different stakeholders. While many of the leading opposition groups, including the National League for Democracy (NLD) boycotted the regime’s electoral process, others did choose to participate, and with good reasons. Faced with the dismal prospect of ceding control to the junta’s proxy the Union Solidarity Development Party (USDP) – after decades of discrimination, human rights abuses and oppression at the hands of the Burma Army and local authorities – political activists in Burma’s ethnic nationality States chose to form parties and participate in the elections in an effort to claw back power, at least in the local context.

Many of those participating in the parliamentary process argue that the limited political space allowed by the system can over time be broadened. The simple fact that there is now room to even question the government is, in itself, enough reason to be hopeful that the government can, in some situations, be forced to listen, and positively respond to the concerns of the opposition parties. The creation of the 14 regional assemblies will at least now enable the long-marginalized ethnic groups to have a say in local politics in a way that would not threaten the military’s grip on central power. In his inaugural address to the Union Parliament, President Thein Sein said, “The centralization has been reduced and states and regions have been entrusted with rights and powers. They will have to take charge of their own duties.”

This remains to be seen, as Thein Sein’s words cannot be taken at face-value, given the long history of broken promises by the previous regime, in which he played a key part.

Another area of uncertainty in Burmese politics is the role of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD, which has no voice in the new parliament after the 1990 election-winning party was disbanded for opting to boycott the 2010 election, along with other political opposition parties. While the NLD’s core movement now seems to focus on social activism, the party can find its true strength by providing not just moral leadership, but one that offers concrete and pragmatic strategies towards a genuine process of democratization in Burma.

Meanwhile, it is vital for the pro-democracy opposition groups and ethnic groups both in exile and inside the country – including those now working within the ‘new’ political structure – to not get bogged down in an endless retrospective debate over the merits of ‘participation versus boycott’, but rather to find a way to work together in a manner that complements each other’s efforts. While the strategies of the two camps – within and outside of the new structure – may be different, they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. After all, everyone shares the same goal of affecting genuine democratic change in Burma.

Salai Nyein Chan

The author holds a Master of Arts (M.A) degree in political science.