Chin Facial Tattoos: Interview with Shwekey Hoipang

31 January 2011 [Note: Chin facial tattoo, mostly practiced among women in the southern parts of Chin State, has now become one of the vanishing traditions in Burma. There are a variety of Chin facial tattoos in terms of forms and styles.

In this interview, Chin Christian pastor of Dai Chin ethnicity from southern parts of Chin State, Shwekey Hoipang talks to Van Biak Thang of Chinland Guardian about different kinds of facial tattoos mostly being practised in Dai areas of Chin State, how they are done and the materials used during the tattoo processes.]

Chinland Guardian: Facial tattoos among the Chin women have gained much attention from tourists around the world. Why is it so special and why do you think people should be so interested?

Shwekey Hoipang: The practice of tattoo is a global cultural phenomenon. In the melting pot of history and myth, its origins are impossible to trace with any certainty. The tattoo culture has been discovered in ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Roman times. Today the tattoo culture is still practised in every continent including the Arctic Circle. It is practiced among celebrities, educated people, religious leaders and many tribal peoples.

Many reasons can be given as to why the tattoo culture has become so well established. Religions can create the need for a distinct identity but many cultures are attracted to the simple belief that decorative tattoos create beauty. Many different styles of tattoo exist and every part of the body, including the face, has been adopted by tattoo cultures.

Chin people are descended from the Mongoloid stock and the Tibeto-Burman family which has spread into Indo-China. The oral traditions held by the Chin people believe they originated from China. Interestingly, the evidence of a facial tattoo culture exists in China and some Indian states. For example, the Dulong tribe in Yunan Province in the Republic of China practised facial tattoo until 1975. Likewise in India, the Desia Kondh tribe from Orissa, Srikakulam and Andra Pradesh States also practise the facial tattoo. It may be significant to note that Indian and Chinese tribal facial tattoo styles are similar to the Chins’.

In Burma, it is mainly Shan, Bamar, Naga and Chin people groups which practise the tattoo. Most of the Shan and Bamar tattoos are in connection with their Buddhist religion beliefs. Tattoos on thighs, especially by males, are proof of heroism, manliness and religious belief. Shan men tattoo on their chest, spine, back and arms because they believe the tattoo can protect them from harm and bad karma. They also believe their tattoos can have magical power in their lives. Slight differences in style exist in the facial tattoos between the Chins and Nagas but they differ greatly from that of the Bamar and Shans.

Today the facial tattoo culture of the Chin people attracts international tourists, photographers and anthropologists, and it has become a subject of research by Burmese academics, historians and politicians. In my opinion, there are commercial reasons for this interest but also, there is a recognition that the tattoo culture will one day be extinct and the opportunity for research is disappearing.

Chinland Guardian: Even among the Chin people as a whole, those in the north do not seem to have tattoos on their faces. What could be the reasons why only women in the south have tattoos on their faces?

Shwekey Hoipang: Yes, it is a good question. The Chins in the northern parts of Chin State do not practise tattoo but those in the south and in the plain areas of Burma do. There is still no scientific explanation based on research. And any attempt which relies on myth makes the answer very uncertain. My honest answer is to say that apart from the mythology, I do not know why the Chins in the southern parts of Chin State, and in plain areas (myaypyant) of Burma practise facial tattoos and those in the northern part of Chin State do not.

Chinland Guardian: So, tell us more about the Chin facial tattoos mainly practised among the Dai Chins?

Shwekey Hoipang: The word tattoo is mang in Dai-Chin. The word mang simply means dream. Once upon a time, a Dai-Chin lady dreamed of having a tattooed face. God (Pangsim) gave her instructions on how to perform the tattoo and its styles. There are several names for tattoos on cheek, forehead and so on; each area of the facial tattoos carries its own meaning and blessing. The tattooist is called mangshun or makshun and, as I mentioned, the tattoo itself is called “mang.” The Dai-Chin females practice facial-tattoo (hmai-mang) and calf-tattoo (kho-mang).

According to Chin myth, there are three theories or reasons for facial tattooing: firstly, to prevent Chin beautiful girls from the Burmese King to be his concubines; secondly, to exercise faith in the traditional animistic beliefs of Chin people in the need for a spiritual safeguard; and thirdly, to enhance beauty as a fashion.

The first theory is difficult to prove scientifically without documentary evidence. The oral tradition says Chin girls were always more beautiful than any other neighbouring tribes. One Burmese King saw a beautiful young Chin girl and asked her parents for permission to marry her. However, the Chin leaders did not want the Chin girl to marry the Burmese King. The Chin leaders then decided to introduce facial tattoos to protect the Chin girls and prevent them from marrying outsiders. I am not sure if this is the true origin of the facial tattoos.

The second theory may have a stronger basis in fact for explaining the origin of Chin facial tattoo. According to my mother’s lullaby and Dai-Chin oral history, the Dai-Chin tattoo is directly connected to animism – the traditional primitive Chin religion. It was believed that a woman without a tattoo who passes away and enters the spiritual world realm will have to stand in front of the judge (Monuoi – in Dai Chin dialect) at the entrance gate of Heaven (Mopi).

For human spirits, life after death involves entering one of the two different worlds, Heaven (Mopi) and Hell (Yapi). The Monuoi gives the ones who have facial tattoo permission to enter Heaven. The Monuoi denies those without a tattoo permission to enter heaven. Afterwards, the spirits of all abnormal and bad people will immediately be sent to Hell (Yapi) by the heavenly judge (Monuoi). For the Chin men, the requirements to enter the Heaven depend upon the correct celebration of feasts and practise of arts that will surely get a token to enter Heaven. A facial tattoo is therefore a spiritual safeguard for Chin females.

The third and last theory is also a good reason for the Chin facial tattoo. Most Chin girls are willing to endure a facial tattoo voluntarily because, despite the pain endured to receive it on their faces, it is believed a facial tattoo makes them beautiful. The Chin facial tattoos are identical in colours despite slight differences in styles. A young Chin lady with a beautiful green-blue colour facial tattoo can be the most attractive one in the community, and she would receive attention from most of the young men. To grow up without having a facial tattoo was regarded as being abnormal, as if resulting from a mental or physical disability. This is unfortunate but it would have been the Chin cultural point of view.

Chinland Guardian: In a travel documentary to Chin State by Burmese actor Lwin Moe, a Chin lady with tattoos on her face was seen in the interview saying that she thinks other women without facial tattoos are ‘unattractive’. What is the meaning behind this?

Shwekey Hoipang: Yes, Burmese actor Lwin Moe did a great job in making a series of travel documentaries in Burma. I really appreciated him for it. I do not know if it is a fair comparison to make but I still want to compare him with Michael Palin, an English television presenter best known for his travel documentaries.

Lwin Moe was fascinated with facial tattoo culture and conducted interviews with Chin women from several tribes about their facial tattoos. Before making his travel documentary to Chin State, I believe he had never met with Chin ladies having tattoos on their faces. After watching a few times, I found it is a great documentary film, apart from some errors in the interpretation.

Lwin Moe met with Chin ladies from Mindat area who have facial tattoos and large earrings. He also interviewed Mkang-Chin, Dai-Chin and Mün-Chin (Cho-Chin) ladies but unfortunately, he had no opportunity to meet Umpu-Chin, Ng’Yah-Chin, Chinpung and Plain-Chin ladies because some of them live in the interior parts of southern Chin State where no access is possible due to remoteness and lack of transportation.

Yes, he interviewed the Mün-Chin lady and she was proud of the beauty of her facial tattoo. She believes it represents the beauty of Chin ladies. Like make-up and other facial decorations, she is also pleased with the colour of her facial tattoo. To Chin men, ladies without facial tattoos are unattractive and in the past, Chin men preferred Chin girls with a facial tattoo. It created an attractive chemistry between young Chin men and girls.

Chinland Guardian: Are there still many women with facial tattoos in Chin State and is it still being practised among the Chin women in the new generation?

Shwekey Hoipang: Yes, there are still many Chin ladies with facial tattoos. Mostly, they are in their 40’s (the younger ones). Apart from a few Chin girls in the jungle villages where traditional animism still exists, the younger educated generation of Chin girls do not practise facial tattoos anymore. Nowadays, it is very rare to see a Chin young girl who is willing to have a facial tattoo.

After the popular 8888 nationwide pro-democracy uprising in Burma, the then Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma led by General Ne Win was taken over and thereafter, there was no proper government in Burma for several months. At that time the two Dai-Chin female tattooists wasted no time in re-introducing the practice of facial tattoos among women in the Dai-Chin areas as they knew there was no authority to arrest and punish them.

As a result in the end of 1988, a senior Dai-Chin female tattooist managed to have tattooed six young Dai-Chin girls including her own daughter as she believed there was no government to ban facial-tattooing in Dailand. After two months, the police in Mindat Town heard about her activities and travelled for three days to see her. But they found that she was too old to appear before court and to be put to jail. Therefore, she was forgiven for her crime of tattooing and given further warning not to do it again.

In early 1989, a junior Dai-Chin old female tattooist tattooed another eight Dai-Chin girls within a month and the news got the attention of the authorities in Mindat. She was arrested, prosecuted and then sentenced to six-month imprisonment. Whilst in prison, she composed some songs reflecting the pride and dignity of Dai-Chin tattoos. Some people still sing her songs whenever they think of our culture and way of life.

There are no more tattooists and no more facial tattoo culture in Dailand with the advancing influence of civilisation, religion and government policies. The 21st century civilisation reaches out to Dailand and thus, Dai-Chin girls are now unwilling to have a facial tattoo. In the same way, Christianity has reached the people and almost all the Dai people are Christians. The Dai-Chins no longer see facial tattoos as a beautiful fashion or as a spiritual safeguard. Furthermore, the government does not encourage facial tattooing.

Chinland Guardian: Do you, as a Chin, fear this tradition will disappear in the future?

Shwekey Hoipang: Yes, it worries me that one day the Chin facial tattoo will totally disappear. Chin young ladies do not want to get a facial tattoo anymore because of various reasons including the pain, the primitive tradition, cultural changes, education, western and Burmese civilisation and religion. The Chin facial tattoo colour is permanent and can never be changed until the tattooed person dies. Today, Chin girls like to decorate their faces with thanatkha, make-up and lipstick. Contemporaneously, there are no more Chin facial tattooists.

In the 1960-70s in my region, there was a kind of cultural revolutionary movement happening under the leadership of Pu Za Hoe (Za Hu), Myopaing Pu Thawng Mang and Myopaing Pu Aung Thang. They introduced new regional laws to stop tattooing, animal sacrifices, retaliation and unwanted child disposal. In particular after imposing the new regional laws, almost all the tattooists were arrested and fined if they performed tattoos. Both the tattooist and girls with tattoos were arrested, fined or put to jail.

In addition in late 1960s and early 1970s, Christian missionaries reached the southern parts of Chin State. With hard works and sacrifices by the faithful pioneer missionaries, the Dai-Chin people were converted to Christianity en masse; within a decade, almost all the Dai-Chin became Christian. All the girls, who were born after the 1970s, preferred not to be tattooed and enjoyed life without a tattoo. Today, some Chin ladies with tattoos feel shy to go out to the city because of the ‘uncomfortable’ attention made to them by the public and subsequently, their children feel embarrassed and ashamed of their tattooed mothers.

As for me, I do not see the gradual extinction of Chin facial tattoos necessarily as a bad thing because the world is changing; all cultures are changing and developing every day. Chin facial tattoo can also become a harmful form of decoration which is hazardous to health because of its associated infection. Some Chin girls died during the tattoo process in the past.

Chinland Guardian: Tell us more about what materials are used and how the tattoos are done.

Shwekey Hoipang: Before I can describe what and how materials are used to perform a tattoo, it is important to know the fact that the Chin parents must go to the tattooist and ask politely for her kind help. The tattooist enjoys the respect given to her and can feel proud of herself. If she is not happy with the family or clan, she can easily say “no”. It is a difficult art and there are not many tattooists. Unless the village is too small, there is normally at least one tattooist available. If the parent is refused by the tattooist from the village, or there is no tattooist in the village, they must take their daughter to another village. The fee is always expensive and can also vary depending upon the tattooists. The cost may range from a big male gayal or mithan (shuishe in Dai-Chin and sial in other Chin dialects) to a big male pig, chickens, blanket and necklace.

After getting an agreement from a tattooist, the parents will go to see the shaman (Tayü) in the village to foretell the future, and get advice for guidance on the best way to perform the tattoo and on other issues including health and safety. The shaman will predict the blessed date for tattooing and give advice on the need of performing all the animistic religious rituals for the girl so that she may not be harmed and may become very beautiful when the tattoo is successfully healed. It is believed all these traditional procedures be followed to ensure that she will be blessed and become attractive to boys. Otherwise, she may end up with scars or a bad colour on her face if the tattoo is not successful.

The animistic religious rituals for a tattoo may include sacrificing animals to the guardian spirit of the household. The meat is eaten together by a few family members and the shaman. Afterwards, the girl is brought to a house on the outskirt of the village and stays there with her mother and her aunties for the night. Green leaves are attached to the front gate to prevent strangers from entering the house. If, by accident, someone went into the house, he or she must pay all the costs for the ritual and for the sacrificed animals.

Very early the next day, the tattooing must be started by the tattooist. Her parents and her female relatives must be with her in the tattoo house to make sure that the girl does not run away as she is going to cry in pain. The female relatives and her father (the only male) may need to hold the girl so that the tattooist is free to get on with the tattooing. Some girls willingly endure the pain whilst others find it too much to bear. The process normally takes one day but this can be extended to two days if the girl reacts in resistance a lot.

The recovery process may take at least two weeks. Her mother and her aunties have to stay with the girl during the healing process. At this time, no strangers are allowed to visit or to pass the house. In order to reduce the chance of getting infection, she has got to stay away from large fires which produce clouded smokes in the village – it is not allowed to make such fires in the village. After two weeks, the dead skins can be peeled off and the new skin underneath would turn blue-green, black-green or black in colours. Gently, she can wash her face with warm water for at least a month until the maturity of her new facial skins. At the end, people then praise her for the beauty of her new facial tattooed skin.

The tattoo materials are very simple and locally available, namely:

1. Pong-hnah (very smooth grass leaves from the farm)

2. Mui-ng’hling (cane-thorns from deep forests)

3. Ng’hlo (colour leaves from the farm)

4. Sungküng (soot from the kitchen)

5. Umkoi (gourd, which is used as a water container) and

6. Am (clay pot).

Pong-hnah: It is a leaf of grass that grows up naturally after slashing and burning the bamboo forest to create new fields for cultivation. The young shoots and leaves of the pong are very smooth, soft and clean. The dirt cannot stay on it. It is best known for its cold sensation and gentleness. Locally, it is used as tissue papers or medical cottons for wiping the blood from the face and covering the tattooed area until the dead skins come off and new skins grow.

Mui-ng’hling: It is used for pricking and drawing all over the girl’s face along the blue-printed marks. Meanwhile, the thorns of the cane have been prepared over one or two months by the parents or by the tattooist. Two or three or up to seven thorns are tied together and dried in the heat of the sun so that they become sharper, stronger and free of bacteria. There are several kinds of canes but the tattooists always prefer using the thorns of royal-cane (Mkongmui-hling) because it is stronger and sharper than any other canes.

Ng’hlo: It is a very important material and is used for colouring cloths and for tattoo. The young shoots and leaves of the Ng’hlo are squeezed and the juice is collected into a small clay pot and gently boiled before being allowed to cool down. The colour of Ng’hlo is normally green-blue.

Sungküng: It is used for the purpose of killing bacteria, for healing the injured skins and helping dead skins to dry out quickly. The tattooist collects the soot from the kitchen and then mixes with water. After all the dirt is removed, it is kept inside a piece of gourd. The diluted sungküng liquid makes it more painful as it contains potash. However, it protects the girl from getting infected by killing bacteria.

Umkoi: It is used as a container for keeping the ng’hlo and diluted sungküng. Mixing the two liquids produces either dark-blue or green-blue ink.

Am: It is used for boiling the Ng’hlo juice. After being washed properly, the clay pot is used for keeping all the tattoo materials including cane thorns and smooth leaves. It is washed properly and used as the container throughout the tattooing processes.

Getting all the tattoo materials ready and upon completing all the required rituals for the girl, it is time for the tattooist to start her parts. The girl may lie down upward and is covered with Yih (blanket) from her chest to toe and held by her mother, aunts and women relatives. The tattooist will spread the mixed ink in squares evenly on the girl’s face. The lines around the squares are tattooed first to create a framework or blueprint which is then filled up with spots and dots until all the squares are carefully and evenly filled. The face is then ready to be applied with mixed ink on every spot and dot. Tattooing simply means inserting mixed ink into the skin through using locally prepared cane-thorns after the blood is wiped. The insertion of cane-thorns must not go too deep inside the skin.

The age of the expert tattooists is mostly between 50-60 years. The tattooing season is in winter from October till February of the year.

Chinland Guardian: Is this practised only among women? At what age should a girl get a facial tattoo?

Shwekey Hoipang: The Chin facial tattoo is practised only by Chin females. When a Chin girl, aged between 12 and 14, reaches puberty, she is considered old enough to be tattooed and enter into an adult life. If the process of tattooing is left too long, the facial skin matures and can become too hard for tattooing. It also makes it too painful when tattooed.

Chinland Guardian: How many kinds of tattoos are there and do they have particular meanings?

Shwekey Hoipang: Chin facial tattoos involve various forms and styles. We can take an example from among the Chins from the plain Chin (Asho) of Burma and southern parts of Chin State. The Plain Chin (Asho or Myaypyant Chin) includes: Sumtu (Cumtu), Laitu (Laytu), Siptu (Sittu), Kawngtu, Khamaw and Asho. The Southern Chin includes: Mün (Cho), Mkang (Kang), Dai, Chinpung, Hmoye, Ng’Yah and Umpu (Uppu). The Matu Chin also once practised facial tattoos but only on the forehead and chin with a few straight lines. The Khumi, Mara, Lautu and Zotung have never practised tattoos.

Mainly, there are two kinds of facial tattoo styles. The Mün tattoo style involves straight lines from forehead to neck with circles between the straight lines and small dots on the forehead and chin. The colour is mainly black and lighter. The Dai, Mkang, Ng’Yah, Umpu, Chinpung, and all the Plains Chin, have the same tattoo styles except for slight differences in the density and lightness of the colours. They all tattoo on their faces but not on their necks; several squares are drawn on the face and these are densely filled with dots. Colours can vary slightly but Dai women favour dark-blue and green-blue colours.

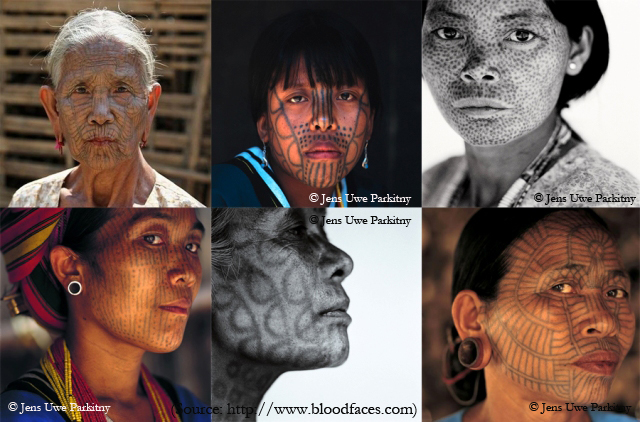

German photographer Jens Uwe Parkitny made several visits to Chin villages and took photos of facial tattoos. He also wrote a book on the Chin facial tattoo called “Blood Faces – Through the Lens: Chin Women of Myanmar”. It was published by Flame Of The Forest Publishing Pte Ltd in 2007. He praises Chin facial tattoos as beautiful art and gives them special names to describe their particular appearances such as Lizard Geometry, Leopard Skin, Spider Web, Spinsters, Pumpkin Skin, Tiger Eyes and Whiskers.

To summarise, it is true to say that Chin women practised facial tattoos because of religion, tradition, culture and fashion. There is something ancient, unique and special about the Chin tattoo culture and, in some ways, the fact that it is dying is a source of sadness. The government’s regional laws, Christianity, intellectual modern civilisation, development and fashion have all contributed to the vanishing colour behind the Chin facial tattoos.

Shwekey Hoipang, a pastor and evangelist, is currently studying Master of Arts in Theology Studies at University of Wales Lampeter in UK. He has also been actively involved in Burmese political movements as well as raising awareness of ethnic issues including religious persecution and human rights violations perpetrated by the ruling military authorities in Burma. For further information about the Chin facial tattoos, he can be reached on 0044 (0)7828057040 and at [email protected].

Bibliography

Jens Uwe Parkitny, Blood Faces – Through the Lens: Chin Women of Myanmar. Singapore: Flame Of The Forest Publishing Pte Ltd, 2007.

Nicolas Thomas (Edits), Tattoo: Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West. London: Peaktion Books, 2005.

Jane Caplan (Edit), Written on the Body: Tha Tattoo in European and American History. London: Peaktion Books, 2000.

Richard Diran, The Vanishing Tribes of Burma. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson Publishing, 1997.

F. K. Lehman, Structure of Chin Society. Urbana: The University of Illinois Press, 1963.

Captain G. C. Rigby, History of Operations in Northern Arakan and the Yawdwin Chin Hills – 1896-97 with A Description of the Country and Its Resources, Notes on the Tribes, and Diary. Rangoon: Government Printing Press Burma, August 1897.

Newspaper & Helpful Websites

- Xinhua News Agency August 16, 2002

- http://www.henan.china.cn/english/2002/Aug/39799.htm#

- http://www.chinesetattoos4u.com/Tattoos-in-Chinese.php

- http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2007-12/25/content_7314483.htm

- http://www.indiasite.com/orissa/orissatribes.html

Interviews

- Saya Ling Lwin Dattui – Dai-Chin Historian (Headmaster of State Primary School, Thingkong Village, Paletwa Township)

- Pu Ling Hung Yongca (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) – Dai-Chin Historian (Khengimnu Village, Mindat Township)

- Pu Ling Kee Dai (Norway) – Dai-Chin Historian (Originally from Shihyüng Village, Mindat Township)

- Saya Tam Ngai Kee – Cho-Chin academic and historian (Private English Tutor – Yangon)

- Salai Cho Mana – Kanpetlet-Chin Historian (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia)