Burma at crossroads

04 March 2011 [CG Note: Burma’s political dynamics are changing along with the political playing field. But the military is still firmly in control, and perhaps even more so than before, as the notion of military supremacy is now formally and constitutionally entrenched. Ironically, the Burmese military regime is pursuing two opposite paths towards building a “modern and developed nation,”: democratization and militarization. But there is still room for “talks” before the current uncertainty reaches a new deadlock, argues Dr. Lian Sakhong.]

INTRODCUTION

For the second time in 20 years, the military regime in Burma conducted general elections on November 7, 2010. The first election was held in May 1990, two years after the nation-wide popular uprising that toppled General Ne Win’s one-party dictatorship, but the outcome was the opposite of what the regime expected, and the result was therefore annulled. The second election was held as part of the regime’s seven-step roadmap, which aims to perpetuate the continued dominance of the armed forces in the new government. This time the result seems to be what the ruling generals wanted to achieve, and they promptly convened the first parliament on 31 January 2011.

The first sitting of the parliament in 22 years was meant to be a watershed, with the introduction of a new form of civilian government to replace the past two decades of naked military rule. Critics claim, however, that it is nothing more than a thinly disguised military dictatorshipi. The military, according to a new constitution adopted in 2008, “remains above the law and [is] independent from the new civilian government.” ii The counter argument to such criticism is that although the general election does not resolve sixty years of political crisis, it can produce “. . . important outcomes and indicators” towards reform. They argue that the “new government will lay out the landscape of a new era of parliamentary system” with some structural changes: a new president, parliament, civilian government and regional assemblies. For the moment, opinions are divided between those “who believe that the new political system marks a first step from which democratic progress can be made and those who argue that the new government must be opposed.”iii

Burma is at a crossroads: as a critical moment approaches, uncertainty increases. Will the new government be the SPDC in a new guise, or will it be a platform from which multi-party democracy can truly spread? Can this new civilian government, under the military constitution, bring democracy, peace and justice? What will be the role of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her NLD party? How will a new government affect the current ethnic conflicts in the country? What will be the role of the international community?

BACKGROUND: POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT SCINCE 1988

In March 1988, a brawl in a tea shop, which led to the death of a student at the hands of the Police, resulted in violent campus wide disturbances. The government responded by closing all the universities and in an attempt to calm the situation promised an inquiry. Believing the environment to be more stable, universities were reopened in June. However, violence once more broke out at the failure of the government to bring to justice those responsible for the student’s death. Unrest soon spread nationwide and martial law was declared. A general strike on the 8th of August 1988 was bloodily suppressed with thousands of demonstrators and students gunned down in the streets. On the 18th September student led demonstrations were once again brutally crushed and soon gave way to an army staged coup.

The army, under the guise of the ‘State Law and Order Restoration Council’ or SLORC, led by General Saw Maung, abolished the Pyitthu Hluttaw and quickly moved to assure the public of it intentions. On the 21st of September the government promulgated the ‘Multi-Party Democracy General Elections Commission Law No. 1/88’ and six days later ‘the Political Parties Registration Law’. On the same day the National League for Democracy was formed with the aim of ‘establishing a genuine democratic government.’ The NLD was led by Chairman U Aung Gyi; Vice Chairman, U Tin Oo, and General Secretary Daw Aung San Su Kyi. Altogether 233 parties were registered to contest the 27 May 1990 election.

To participate in the election the BSPP changed its name to the National Unity Party and also began to canvass. However, it soon became evident that the NUP was losing to the National League for Democracy, especially due to the popularity of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. After slanderous attacks on her in the media had failed, the government had both Aung San Suu Kyi and U Tin Oo arrested on the 19th July 1989. Despite the fact that two of its main leaders were under house arrest and disqualified, the National League for Democracy was still able to win 392 (80%) of the 485 seats. The military-backed party, the National Unity Party (NUP), won only 10 seats (2%). The balance of power was held by the ethnic parties, the United Nationalities League for Democracy (UNLD) – 67 seats (16%) and 10 independents (2%).

Despite the party’s clear victory, the SLORC refused to hand over power to the NLD claiming that a constitution needed to be drafted first. The NLD and the newly formed United Nationalities League for Democracy (UNLD), an umbrella group of ethnic party representatives, issued a joint statement calling on the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) to convene the Pyithu Hluttaw in September, 1990. Despite such calls the SLORC refused to honour the election result and instead sought to hold on to power claiming that a National Convention would need to be convened to write a new constitution.

After two years of political impasse, and with members of the NLD still in jail or under house arrest, the SLORC announced, on the 23rd of April 1992, that it would hold a National Convention – the six main objectives would be:

- Non-disintegration of the Union;

- Non-disintegration of national unity;

- Perpetuation of national sovereignty;

- Promotion of a genuine multiparty democracy;

- Promotion of the universal principles of justice, liberty and equality;

- Participation by the Defense Services in a national political leadership role in the future state.

On the 28th May 1992 a National Convention Steering Committee was formed to write the new constitution. The committee included 14 junta officials and 28 people from seven different political parties. The committee named 702 delegates. Of these only 99 were elected Members of Parliament and seventy percent of the delegates were township level officials handpicked by the military.

After constant suspensions and reopening, delegates had agreed 104 principles with ethnic representatives still attempting to secure a federal system. In an attempt to ensure that Aung San Suu Kyi would have no political role in the government of the country the convention law stated, despite opposition from many of the delegates, that the president of Burma must have been a continuous resident for more than 20 years, have political, administrative, military and economic experience and not have a spouse or children who are citizens of another country.

On 29 November 1995, in response to criticism from the National League for Democracy, the Military regime expelled all of the NLD delegates from the assembly resulting in the number of MPs elected in 1990 becoming less than three percent of all delegates. The convention was once again suspended and the constitutional process stalled until the appointment of new Prime Minister Khin Nyunt in 2003. The new premier unveiled what he called a seven-step roadmap. The seven steps were:

- Reconvening of the National Convention that has been adjourned since 1996.

- After the successful holding of the National Convention, step by step implementation of the process necessary for the emergence of a genuine and disciplined democratic system.

- Drafting of a new constitution in accordance with basic principles and detailed basic principles lay down by the National Convention.

- Adoption of the constitution through national referendum.

- Holding of free and fair elections for Pyithu Hluttaws (Legislative bodies) according to the new constitution.

- Convening of Hluttaws attended by Hluttaw members in accordance with the new constitution.

- Building a modern, developed and democratic nation by the state leaders elected by the Hluttaw; and the government and other central organs formed by the Hluttaw.

In the face of open criticism from a number of parties, both within and outside of the country, including Kofi Anan, The U.N. Secretary General, the National Convention reconvened on the 17th May 2004 with 1,076 invited delegates including representatives from 25 ethnic ceasefire groups.

The National Convention was concluded, after 14 years of deliberation and several sessions, on the 3rd of September 2007. On the 9th of February 2008, the SPDC stated that a National Referendum to adopt the constitution would be held in May 2008. In spite of the fact that Cyclone Nargis struck the country on the 2nd and 3rd of May 2008 causing widespread devastation, the regime insisted on continuing with its plan to hold the referendum, except for a few townships where the destruction occurred most, on the 10th of May 2008. The regime announced that the draft Constitution had been overwhelmingly approved by 92.4 per cent of the 22 million eligible voters, stating that there had been a turnout of more than 99 per cent.

As the fifth step of the seven-step roadmap, the regime conducted general elections on 7 November 2010. The election was particularly flawed. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was still under house arrest and ineligible to contest due to an election law that excluded electoral participation by any member of a political party who has been convicted in court. In addition, the Union Election Commission (UEC) stated the Kachin State Progressive Party (KSPP) was ineligible to register because of connections with armed ceasefire group, the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) effectively ensuring that only regime candidates were able to contest the election.

THE CURRENT PROBLEM: A TWIN PROCESS OF MILITARIZATION AND DEMOCRATIZATION

The regime political objective is clear: the domination of armed forces, Tatmadaw, in the new government. As stated in its seven-step roadmap, the armed forces will “participate in the national political leadership role of the state”. As Sr. Gen Than Shwe frequently said, the goal of the regime’s political roadmap is “national reconsolidation”, not “national reconciliation”, which will be implemented through a twin process of “militarization” and “democratization”. This twin process is a combination of two different political systems that mutually oppose each other; a mixture of uncertainty, danger and hope. Although the twin process is a dangerous and unpredictable mix, some activists believe that it can open a window of opportunity, at least for a long term gradual transition, instead of maintaining the status quo.

In a Burmese political context, the concepts of “national reconsolidation” and “national reconciliation” are totally different. National “re-consolidation” or “consolidation” is meant to be the establishment of a homogeneous country of Myanmar Ngaing-ngan, with the notion of “one ethnicity of Myanmar, one language of Myanmar-ska, and one religion” or a state religion of Buddhism as the saying goes: “Buddha-Bata Myanmar-Lumyo” (To be a Myanmar is to be a Buddhist). National reconciliation, on the other hands, is meant to be the establishment of a genuine federal union where many ethnic nationalities from many different religious, cultural, linguistic and historical backgrounds can live peacefully together.

In order to build a homogeneous nation-state of Myanmar Ngain-ngan, the regime designed the military domination of the state in the 2008 Constitution but in the name of “democratization” it chose the “seven-step roadmap” to democracy. In accordance with the seven-step roadmap, the regime conducted the national convention, adopted a new constitution through a national referendum, held general elections, convened a new parliament, and will install a civilian government. They argue that implementing the process of the “seven-step roadmap” is part of the “democratization” process.

Within the same objective of “national reconsolidation”, the regime has designed another process, that of “militarization”, which goes hand in hand with the so called “democratization”. In order that the military takes the leading role in national politics, the 2008 Constitution was designed in such a way that the armed forces would remain above the law and be independent from the government, and, therefore, would dominate and control the three branches of political power.

To control the legislative power at both the Union and State and Regional Assemblies, the 2008 Constitution reserves 25 percent of the seats in all legislative chambers for the military personnel’s. In this way, according to the 2008 Constitution, a total of 386 military personnel will be appointed as lawmakers; (110 out of 440 seats for lower house; 56 out of 224 seats for upper house; and 220 out of 883 seats for 7 states, 7 regions and 3 autonomous regions)iv.

In addition to the constitutional arrangement, which is designed for military domination, the regime also formed a proxy party called the “Union Solidarity and Development Party” (USDP). In the 2010 general elections, the USDP won 76 percent of the total vote, 79 percent of lower house seats, 77 percent of senate seats and a 75 percent stake in the seven state and seven regional assemblies. Since the military is controlling the legislature power at all levels, it will be very difficult to make any changes in the 2008 constitution, which requires the backing of more than 75 percent of parliamentary votes for constitutional amendments.

The executive power of the state, according to the 2008 Constitution, will be totally under the control of the armed forces. The President and two Vice-presidents, who are the head of the state and represent the country, will be elected not by the public but by the Presidential Electoral College, consisting of three groups of parliamentarians: upper house, lower house and military appointed lawmakers. Each group will nominate one candidate for the presidency. Members of the Electoral College will then vote for one of the three to become president. The candidate with the most votes takes the top job and the unsuccessful candidates will become vice-presidents. All will serve five year terms. In this way, the military constitution has by-passed the public in presidential election process, but guaranteed the armed forces, as decision makers, participation in the highest level of national politics.

In addition to the 386 military personnel already appointed as lawmakers, the Commander-in-Chief of the Defense Service will appoint three generals as ministers of defense, the interior and border affairs. The president can also select military officers to head other ministries. Armed forces members serving in government, parliamentary or civil service roles accused of a crime will be tried by a military court martial court rather than a judicial one.

The 2008 Constitution creates a powerful body, the “National Defense and Security Council”, consisting of 11- member committee tasked with making key decisions. While the president will serve as the Chairman, military personnel will occupy five of the 11 places on the National Defense and Security Council. In this way, the armed forces will control the decision making process at a political body which is granted the right to declare “state of emergency”.

The “state of emergency” in the 2008 Constitution, unlike a democratic constitution, is a mechanism created for the armed forces to control the state. Through the right to declare “state of emergency” the highest law of the land granted the chief of armed forces the right to take over the state power, or the constitutional right of a military coup. With presidential approval, the armed forces chief can assume sovereign power and declare a state of emergency, with full legislative, executive and judicial power. In this way, the armed forces will remain above the laws and control the state.

This is how the armed forces in Burma, known as Tatmadaw, will engage the process of “militarization” in the name of “democratization”.

THE NEW FACE OF THE MILITARY REGIME

On 15 March 2011, Burma will see a new face of the military regime but it will be in civilian clothes. When a president takes office, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), as the military junta calls itself, will cease to exist.

Ex. Gen. Thein Sein, former Prime Minister of SPDC, will become the new President of the Union of Burma. Thein Sein, who retired from the army in April to lead the junta’s proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, is Than Shwe’s long term friend and close aide. He replaced former spy chief Gen Khin Nyunt as the junta’s Secretary-1 in Oct 2004 while Gen Soe Win became Prime Minister. In April 2007, while Soe Win was suffering from leukemia, Thein Sein was appointed acting prime minister. When Soe Win passed away in October 2007, he became the permanent prime minister.

Ex-Gen. Tin Aung Myint Oo, a former Secretary-1 of SPDC, and Sai Mauk Kham, a Shan ethnic, will become the two vice-presidents of the Republic of Union of Burma. Tin Aung Myint Oo, as Secretary-1 of the junta, was the fourth most powerful man in the country and assigned in April last year to run the USDP together with Thein Sein. Sai Mauk Kham is also a member of USDP.

Ex. Gen. Shwe Mann, the junta’s third-ranking officials, has been elected as the speaker of the Lower House of Parliament, known as Pyithu Hlutdaw; and Khin Aung Myint, the junta Culture Minister, will become the speaker of the Upper House, known as Amyotha Hlutdaw.

Unlike the president, one vice-president, and two speakers, who are recently retired from army; three active-military generals have also been appointed to key cabinet positions. Burma’s new Defense Minister will be Lt-Gen Ko Ko, a former chief of the Bureau of Special Operations-3. Maj-Gen Hla Min, the current BSO-3 chief, has been appointed Minister of Home Affairs, and Maj-Gen Thein Htay, the chief of military ordnance, is appointed as Minister for Border Affairs. The new Foreign Minister will be Wanna Maung Lwin, a former military officer turned diplomat.

In accordance with the 2008 Constitution, the president, two vice-presidents, two speakers, Commander-in-Chief and Deputy Commander-in-Chief of Defense Services, ministers of Defense, Home Affairs, and Border Affairs will form one of the most powerful bodies of the state, namely, the “National Defense and Security Council”.

In addition to the “National Defense and Security Council”, the military regime is creating another powerful body, known as the “State Supreme Council”, which is nowhere mentioned in the 2008 Constitution. As the name implies, it will become the most powerful body in the country, and will be “. . . above and beyond the powers of the new civilian executive and legislative branches.”v The members of the State Supreme Council will be: Snr-Gen Than Shwe, Vice Snr-Gen Maung Aye, Pyithu Hluttaw (Lower House) Speaker Thura Shwe Mann, President-elect Thein Sein, Vice President-elect Thiha Thura Tin Aung Myint Oo, former Lt. Gen Tin Aye and other two senior military generals.

In such an important body as the “State Supreme Council”, none of the non-Burman ethnic nationalities are included, even the vice-president Sai Mauk Kham is out. So, the new show of military regime in Burma will be run exclusively by ethnic Burman/Myanmar nationals from the Burma Army.

A NEW POLITICAL LANDSCAPE

Whether we recognize it or not, the 2010 election brings a new political landscape in Burma. In addition to the new government, that will be known as the Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, there will be seven ethnic state assemblies and governments plus another seven regional assemblies and governments. This new political scene will create a new political space, either positively or negatively, where many political actors will take part. At the same time, the new reality after election also brought unavoidable change, at least in terms of political structures and functions, within the main opposition groups, especially the NLD and ethnic parties that won the 1990 elections.

Within this newly emerged political scene, the reality of new developments can be recognized, especially within opposition groups and ethnic nationalities, as follows:

(i) Opposition Groups

Since he National League for Democracy (NLD) and United Nationalities League for Democracy (UNLD) members that won the 1990 elections boycotted the 2010 election, the group commonly known as “democratic forces” is unlikely to make any big change within a new political structure created by the 2008 Constitution and the 2010 election in November. The National Democratic Force (NDF), formed by a splinter group of the NLD, won merely 12 seats (2%), and will not be able to make any impact within the parliament. Thus, the opposition groups within the Union parliament will be weak and cannot be expected to be the main players for change.

(ii) Ethnic Political Parties

The 2008 Constitution has created unexpected political structures in ethnic states, namely, the state assemblies and state governments. Although it is far from perfect, these new structures allow the ethnic nationalities for the first time in their history to elect their own representatives for their respective homeland assemblies and state governments. Many are hopeful that these new structures will eventually bring genuine “ethnic representation” for ethnic states in a form of “self-rule” through the federal arrangement of the Union constitution, but how to amend the 2008 Constitution is another blockage to be overcome.

In addition to state assemblies and state governments, the ethnic nationalities in Burma, for the first time in their history, will be able to send equal representatives to the Upper House of the Union Assembly. For this opportunity, they have been fighting so hard for so long; most notably during the “federal movement” in early 1960s. Although the 2008 Constitution does not grant the “right of self-determination” for ethnic nationalities, this arrangement is far better than the 1947 and 1974 Constitutions.

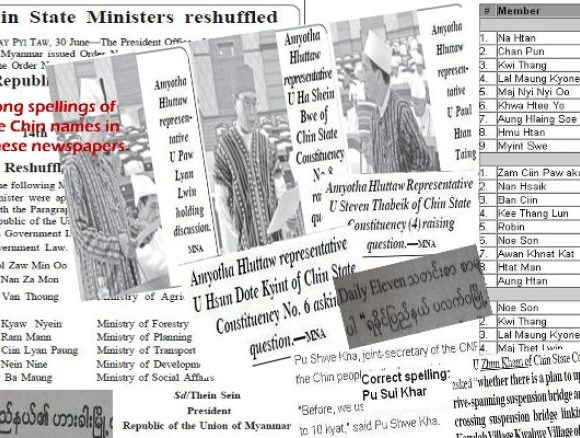

As unexpected window of opportunity present itself, ethnic political parties are prepared to take advantage. In the 2010 election, 16 out of 22 winning parties are ethnic national partiesvi, which can dominate their respective state assemblies between 29% (Mon State) and 45% (Chin State)vii. If it were not for 25% seats reserve for the army and the advance-votes, through which the USDP claimed most of its winning seats; at least four ethnic states, namely, Arakan, Chin, Karen and Shan States, would have been able to form their respective state governments.

Only in the Kachin and Karenni States, local ethnic parties that genuinely represent their peoples were unable to contest. In the Kachin State, the election commission rejected the registration of the Kachin State Progressive Party (KSPP), which is formed and backed by the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), a ceasefire group. In the Karenni (Kayah) State, the All National Races Unity and Development Part (Kayah State) was forced to withdraw its registration due to political pressures.

Although the ethnic national parties do not form a single political platform or a front, similar to the UNLD in 1990, the five parties from Arakan, Chin, Karen, Mon and Shan States recently issued a joint statement in January 2011, calling for “the lifting of sanctions, ethnic representation in the state administrations, and general amnesty” to illustrate that “the military government has ended and democratic transition has begun.”viii

(iii) Ethnic Armed Groups (Ceasefire)

There were as many as 30 different ceasefire groups but only 17 are recognized as “official” or “major groups”. Most of the major ceasefire groups attended the second round of National Convention in 2004-2007, and the 13 groups collectively submitted their proposal to the NC, in which they proposed federal system as the basis for the future constitution of the Union of Burma. The regime, however, ignored their proposal. In 2007, the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), one of the largest groups among the ceasefires, submitted their proposal once again, known as the 19 point proposal, based on the federal principles. This time, the regime not only refused the proposal but threatened to break the ceasefire agreement with the KIO, saying that “they can be pushed back to the mountain.”ix

Since the end of the National Convention, which served as an official platform and the focal point of communications, the relationship between ceasefire groups and the regime began to break down. To make matters worse, the regime issued an ultimatum in April 2009, which demanded that all the ceasefire groups give up their arms and transform themselves into a Border Guard Force (BGF) under government control. The regime also threatened them that any ceasefire group that did not give up their arms by 1 September 2010 would be declared illegal organizations.

Most of the major ceasefire groups wanted to maintain their forces and territories until a political solution is found and the new political system is properly installed. While most of the major groups, including the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), New Mon State Party (NMSP), rejected the regime’s BGF proposal;x at least 9 ceasefire groups accepted to become a BGF.xi Another 8 smaller ceasefire groups are willing to transform themselves as the militia (Pyithusit) under the command of the regime’s armed forces.

Although the deadline has passed, the BGF issue remains a flash point where ceasefire agreements can be broken and thus fighting resume. There are many indicators that suggest that the regime is preparing for a major offensive against those have who rejected the BGFxii, suggesting that the government will use the same tactics employed against the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Party, also known as the Kokang Group, in August 2009. During the clash with Kokang, which lasted only a few weeks, at least 37,000 refugees fled to China.xiii

(iv) The New Alliance of Ethnic Armed Groups: United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC)

As the military regime has accelerated its seven-step roadmap, tensions between ethnic armed groups and the Burma Army have intensified. The BGF issue is the major concern for both sides. As the tension has increased, ethnic armed groups from both ceasefire and non-ceasefire groups have discussed about joint cooperation should the SPDC launch an offensive against them.

In May 2010, the first meeting between the two sides of ethnic armed groups, ceasefire and non-ceasefire, was held. At the second meeting in September 2010, they jointly formed a committee, the “Committee for the Emergence of a Federal Union” (CEFU), comprising of three ceasefire groups: KIO, NMSP, and SSA-N (Shan State Army-North), and three non-ceasefire groups: KNU, KNPP (Karenni National Progressive Party), and CNF (Chin National Front).

In February 2011, CEFU was transformed into the “United Nationalities’ Federal Council” (UNFC). As the “committee” is transformed to the “council” its members increased, from 6 to 10 armed groups with approximately 20,000 troops; and supported its formation process by the Ethnic Nationalities Council (ENC), which is a political alliance of all ethnic nationalities from seven ethnic states. The UNFC and its members are committed to collaboration on political and military matters with the final objective of achieving a genuine federal union of Burma. This has been a solid work in progress over the last decade. The UNFC issued a statement soon after it was formed, and urged the international community “to force the Burma Army to negotiate with the ethnic nationalities in order to find a political solution”. They also declared in the statement that “we will wage unconventional warfare until the Burma Army negotiates.”xiv

WHAT’S NEXT: DIALOGUE OR CONFRONTATION?

In this changing political landscape, what roles will the NLD and UNLD/UNA, the parties that won the 1990 general elections and still enjoy the public support as ever, play? What about the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), and other democratic forces in exile? What role will the ENC play if there is no more room for a negotiated settlement? All these democratic forces and ethnic nationalities’ organizations have been advocating so long for a peaceful transition to democracy in Burma. But what will be their new roles in a rapidly changing political context in Burma?

An essential question, however, is not what roles they would play but what choice Burma will make: dialogue or confrontation? If the choice is a peaceful transition to democracy through negotiated settlement and dialogue, then they all still have many important roles to play.

(i) The Second Panglong Conference, or Revival of Panglong Spirit

When the tension between the SPDC’s Army and Ethnic Ceasefire Armies was high, the ethnic issue was cast dramatically in the limelight. Another aspect of in relation to ethnic issues was made by the UNLD/UNA. It issued a statement in October 2010 calling for a Second Panglong Conference.

Although the call for a Second Panglong Conference was nothing new, the significant this time was the endorsement they received from the NLD leadership, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, U Tin Oo, U Win Tin, and others. One of her first major political statements since her release in November 2010, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi strongly endorsed a call for a Second Panglong Conference.

Since the eruption of the 1988 democracy movement, both democratic forces and ethnic nationalities have called several times for a Second Panglong Conference. Most notably, the NLD and UNLD jointly called for the Second Panglong Conference in August 1990 when they issued the “Bo Aung Kyaw Street Declaration”. In 2001, the ENC (as ENSCC) launched a campaign called the “New Panglong Initiative”, in order to rebuild the Union based on the spirit of the 1947 Panglong Agreement. Recently, the KIO also called for the revival of the Panglong Spirit to end six long decades of civil war and political conflict.

The Panglong Agreement, which was signed on 12 February 1947, was an agreement on which the Union of Burma was founded in the first place. For the ethnic nationalities and democratic forces, the revival of the Panglong Agreement means re-building the Union of Burma based on federal principles that will guarantee democratic rights for all citizens, political equality for all ethnic nationalities, and the rights of internal self-determination for all member states of the union. As such, so long as Burma is under a military dictatorship and applies the military constitution of 2008 the need for the revival of the Panglong Spirit will be there. Thus, all democratic forces and ethnic nationalities should be united in calling for the revival of the Panglong Spirit until and unless Burma becomes a genuine federal union. This is where the NLD and other democratic forces, under the leadership of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, can play a major role.

(ii) Tripartite Dialogue in Solving Three Issues

In 1994, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution which has been reaffirmed every year since calling for “Tripartite Dialogue” to resolve Burma’s problems and to build a sustainable democracy. According to the UN GA resolution, ‘Tripartite Dialogue’ is meant to be a dialogue amongst:

- The military led by the SLORC / SPDC

- 1990 Election-winning Parties led by the NLD

- The Ethnic Nationalities.

The essence of “Tripartite Dialogue”, however, is not just a “Three-party Talk” but to solve “Three-Issues” that Burma is facing today. These are:

- De-militarization: How to transform the Armed Forces into a normal civil service? How all ethnic armed groups, who have been fighting sixty years of civil war, will be integrated into a normal civilian lives? This is a huge task Burma will face because the regime is still engaged in “militarization”, opposite to the needs of the country and the people;

- Democratization: Since 1962, Burma has been under a military dictatorship, and there are no political institutions which can sustain a free and open democratic society. Democratization, including building civil society and political institutions, is a major challenge for the regime and its new government. If the democratization process succeeds then Burma will be become more or less a free country but if it is fails, then the country will be back to square one: military dictatorship.

- Ethnic Issues: Ethnic Nationalities in Burma have already been engaged in over sixty years of civil war, in order to regain autonomy in their respective homelands there must be a federal arrangement.

Until and unless these three issues are solved, Burma will remain a land of political turmoil, ethnic conflict and civil war.

(iii) The Role of International Community: Multi-Party Talks on Burma

The international community, including the United Nations, admitted that Burma is facing “many political, economic and social challenges and that some of its problems are quite serious,” and Burma is “a threat to regional stability and international peace.” xv At the UN Security Council, even the so called “pro-junta” countries like China acknowledged that Burma, indeed, is “faced with a series of grave challenges relating to refugees, child labor, HIV/AIDS, human rights and drugs,” and suggested that the UN should address those problems through the good offices of the Secretary-General under the mandate of the General Assembly.

The problem, however, is the fact that that the international community does not have a common policy towards Burma. While Western countries prioritize restoration of democracy in Burma, our neighboring countries, especially China, India and ASEAN countries, are concerned more about stability in the country and the region. So long as the international community applies different policies, the pressures from outside, including sanctions, will not be effective.

Since 2007, the Ethnic Nationalities Council (ENC) has been calling for “Multi-party Talks on Burma” under the UN mechanism in order that the international community can adopt a common policy towards Burma. Such a process and mechanism are needed because the members of the international community who are dealing with Burma should consult each other, so that they can take concerted action.

Previously, the regime has taken a stance that it will never engage in Burma issues outside of Burma, and the same hard liners are still around. However, the idea should still be pursued further, especially with the new government. Since the regime has conducted general elections and the new government is going to be installed, it seems that this is the right time to convene an international consultation in a form of “Multi-party Talks on Burma”, as the ENC has suggested.

In such a consultation, many issues, including the following, can be discussed: How could western countries such as the USA and international institutions such as the EC, the UN, the WB, IMF and the ADB adapt their policies to the new situation? How far will the west’s strategy towards Burma depend on Aung San Suu Kyi’s? Shall economic sanctions be lifted? What can be expected from China, ASEAN and other pro-junta players?

CONCLUSION

Burma is at a crossroads; whether to go the path of “militarization” or to “democratization”. The road to “militarization” will inevitably lead the country to political confrontations and ethnic conflicts, including the return to fighting after so many years of ceasefire agreements with ethnic armed groups. Democratization, on the other hand, can be the path to reconciliation, peace and development. Since the military regime is intending to engage these two opposite paths as a twin process in the name of “national reconsolidation”, the situation has become such that a simple choice cannot be made between either/or yes and no.

The best solution seems to be to engage in “talks” before the current uncertainty reaches a new deadlock. As General Saw Maung and General Khin Nyunt promised when they signed ceasefire agreements with ethnic armed groups: General Khin Nyunt, as head of the government said: “We are not really a government, we have no constitution. After we have a constitution, you can talk to the new government.” xvi The democratic forces, led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and ethnic nationalities should stand firm in unity and demand a dialogue with the new government, as was promised. The regime now has a constitution and a new government. Thus, as promised, this is time to talk.

By Lian H. Sakhong

This paper was presented at the Forum for Asian Studies of Stockholm University in the Seminar Series 2011 on 01 March 2011. Dr. Lian H. Sakhong, Research Director of Euro-Burma Office, Brussels, is also the Chairman of “Chin National Council” (CNC), and the Vice-Chairman of the “Ethnic Nationalities Council – Union of Burma” (ENC). He has published several books and numerous articles on Chin history, traditions and politics in Burma and was awarded the Martin Luther King Prize in January 2007.

Appendix (1): Ethnic Parties that won Elections in 2010.

1. All Mon Regions Democracy Party

2. Chin National Party

3. Chin Progressive Party

4. Ethnic National Development Party [Chin State]

5. Inn National Development Party [Sha State]

6. Kayan National Party

7. Kayin’s People Party

8. Kayin State Democracy and Development Party

9. Lahu National Development Party [Shan State]

10. Pao National Organization [Shan State]

11. Phalon-Sawaw (Pwo-Sgaw) Democratic Party [Keren State]

12. Rakhine Nationalities Development Party [Arakan State]

13. Shan Nationalities Democratic Party

14. Tauang (Palaung) National Party [Shan State]

15. Unity and Development Party of Kachin State

16. Wa Democratic Party [Shan State]

Appendix (2): Election results in ethnic state legislatures

The balance of power (expressed in percentages) in the ethnic state legislatures is as follows:

Chin State Legislature

Military 25%

USDP 29.2%

Other (Chin Parities) 45.8% [CNP 20.8%; CPP 20.8%; ENDP 4.2%]

Kachin State Legislature

Military 25.5%

USDP 39.2%

Other 35.3% [NUP 21.6%; SNDP 7.8%; UDPKS 3.9%; Independent 2%]

Kayah State Legislature

Military 25%

USDP 75%

Kayin (Karen) State Legislature

Military 26.1%

USDP 30.4%

Other 43.5% [PSDP 17.4%; KPP 8.7%; AMRDP 8.7%; KSDDP 4.3%; Independent 4.3%]

Mon State Legislature

Military 25.8%

USDP 45.2%

Other 29% [AMRDP 22.6%; NUP 6.4%]

Rakhine State Legislature

Military 25.5%

USDP 29.8%

Other 44.7% [RNDP 38.3%; NDPD 4.3%; NUP 2.1%]

Shan State Legislature

Military 25.2%

USDP 37.7%

Other 37.1% [SNDP 21.7%; PNO 4.2%; TNP 2.8%; INDP 2.1%; WDP 2.1%; rest 4.2%]

(Source: “A Changing Ethnic landscape: Analysis of Burma’s 2010 Polls” (Burma Policy Briefing No. 4, December 2010, by Burma Centrum Netherland)

Appendix (3): List of Ceasefire Groups that rejected Border Guard Force status:

(1) Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (5th Brigade)

(2) Kachin Independence Organization

(3) Kayan Newland Party

(4) KNU/KNLA Peace Council

(5) New Mon State Party

(6) Shan State Army- North/Shan State Progressive Party

(7) United Wa State Army

(8) National Democratic Alliance Army (Mungla Group)

Appendic (4): List of Ethnic Ceasefire Groups that accepted BGF status

(1) New Democratic Army – Kachin

(2) Karenni Nationalities People’s Liberation Front

(3) Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army – Kokang

(4) Lahu Militia (Maington), Shan State

(5) Lahu Militia (Tachilek), Shan State

(6) Akha Militia (Maingyu) Shan State

(7) Wa Militia (Markmang) Shan State

(8) Democratic Keran Buddhist Army

(9) Keran Peace Force (ex-KNU 16th Battalion)

[i] . Cf. Larry Jagan, “This Parliament makes a Mockery of Democracy” (Reuter, 31 Jan 2011)

[ii] . Ethnic Nationalities Council (ENC) Policy Statement, September 2009.

[iii] .Cf. ”Ethnic Politics in Burma: The Time for Solutions” (Amsterdam: Burma Centrum Nederland’s Policy Briefing, No. 5, February 2011)

[iv] . In 2010 general elections, voting did not take place in 4 townships in the areas controlled by thee United Wa State Army; and also two constituencies for state legislature in Kachin State. Thus, according to the Election Commission announcement on 16 September 2010; the elections taken place as follows:

(i) Pyithu Hluttaw (Lower House): 326 constituencies (+ 110 seats for Armed Forces)

(ii) Amyotha Hluttaw (Upper House): 168 constituencies (+56 seats for Armed Forces)

(iii)14 States/Region legislatures: 663 constituencies (+220 seats for Armed Forces).

[v] . Irrawaddy, 10 February 2011

[vi]. See Appendix (1): List of Ethnic Parties that won elections in 2010.

[vii] . See Appendix (2): Election results in ethnic state legislatures

[viii] . The statement is jointly issued by the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party (Arakan State), Chin National Party (Chin State), Phalon-Sawaw Democratic Party (Karen State), All Mon Regions Democracy Party (Mon State), and Shan Nationalities Democratic Party (Shan State), on 15 January 2011.

[ix] . See “The Kachin Dilemma: Contest the Election or Return to Guerrilla Warfare” (Brussels: EBO Analysis Paper, no. 5, 2010)

[x] See Appendix (3): List of Ceasefire Groups that rejected BGF status.

[xi] See Appendix (4): List of Ceasefire Groups that the status of BGF.

[xii] . The Kachin News Agency reported that “At the end of November, senior officers from SPDC met in Myittkyina and discussed preparations for possible war. The situation is volatile and observers felt that China may not be overly concerned with what goes on in Kachin because they are Christians, seen as closer to the United States, and not ethnically Chinese (unlike the Wa and Kokang); KNC, Dec 6, 2010.

[xiii] . Cf. “The Kokang’s Clash: What’s Next?(Brussels, EBO Analysis Paper, September 2009).

[xiv] . UNFC’s Statement, on 17 February 2011.

[xv] . Cf. ”Threat to the Peace: A Call for the UN Security Council to Act in Burma” (Report Commissioned by The Honorable Vaclav Havel, Former president of Czech Republic, and Bishop Desmond M. Tutu, Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town) September 20, 2005. See also the UN Security Council’s Presidential Statement, October 2008, and the ENC Mission State, July 2007.

[xvi] . Cited by Tom Kramer, “Neither War nor Peace: The Future of Ceasefire Agreements in Burma” (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, 2009), p. 13